So far, in our Myth of Macho series, we have seen a plentitude of examples of masculine “durability.” Lee Marvin withstood hell and highwater in the majority of his films, while Arnold Schwarzenegger’s travels through the sci-fi/action genre established his ability to brave more than just the earthly realm. Even films like Lethal Weapon or Full Metal Jacket highlight a certain resilience within male culture. By establishing men as the ultimate in reliability and strength, it is but a hop, skip and a jump to position them against the one thing that would seem to have more power and pose the greatest threat: nature. Within print and visual media, man’s ability to triumph over nature is what has traditionally made him a “real man” as it is the one thing that he cannot control. Much like Pinocchio’s transformation from marionette to genuine boy at the end of the fairytale, if a given story’s male protagonist is able to conquer the chaotic forces of the natural world and maintain authority, his masculinity is not only unblemished and intact but it becomes a thing to be celebrated. He would, by all intents and purposes, fall under the label of “hero.”

In 1923, Tin Pan Alley songwriter Bartley Costello wrote the song “A Fire Laddie (Just Like My Daddie)” wherein the protagonist croons, “Little boys a’playin, one of them is saying, ‘When I grow up I’ll be a soldier bold!’ […] A little curly head said, ‘Not for me, when I grow up, here’s what I want to be, a fire laddie just like my daddy, faithful, big and brave, without a fear when danger’s near, to do to dare and save, a hero when the red fire glows […] with the ladder and the hose.” According to a 2009 survey taken by Forbes, 5 out of 33 Kindergarten-age children reported that they, too, wanted to be firefighters when they grew up. The desire to risk one’s life daily amidst heat, flames and burning buildings has not changed much over the years. The career written about in 1923 is still the same one being dreamt of by little boys today. But what is it that makes firefighting so high up on the list of “dream occupations” for young boys?

For a great percentage of the male population, the reason the firefighting industry carries with it such great allure is because it is constructed out of a real sense of duty mixed in with a sense of heroism that goes beyond everyday action. In a sense, firefighters are real-life superheroes, possessing a certain knowledge and experience that no one else has. They battle fire: a force that seems altogether beyond anyone’s control. As firemen, they work with an element that has a mind of its own and bears a striking resemblance to features of the comic book or supernatural world. No matter how “in control” of a given situation they might be, there is always the chance that the fire-beast may escape and do something entirely different, behave in an anarchic and unexpected manner.

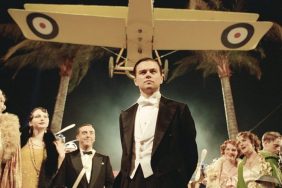

The film that we will be discussing this week is Ron Howard’s 1991 fire-breathing epic, Backdraft. Not only is this film a tale about man versus nature by way of inferno but it also looks at man versus nature by way of familial conflict and heritage. In Howard’s establishment of fire as a primary “character”, the film manages to position itself as a piece that transcends its outward appearance of “Chicago-firefighter-drama,” becoming an action-adventure with heroic overtones. As Backdraft’s structure unfolds, we are introduced to the fiery element that is anthropomorphized by our protagonists. While the film does indeed showcase the male-centered culture of a metropolitan firehouse and its traditions, the rhetoric of “fire-as-sentient-being” places the film squarely in heroic adventure territory as there is now a larger-than-life monster as the adversary. Backdraft is a quick-paced mixture of hypermasculine traditions and fetishized bravery with a little bit of the “fantastic journey” thrown in for good measure.

This film, screenwritten by former fireman Gregory Widen, is a film that divides its narrative between the relationship struggles of the McCaffrey Brothers and the mystery of a serial arsonist setting fires around the Chicago area. Brian McCaffrey lost his father at a very young age, leaving older brother, Stephen, with the responsibility of raising him. Skip forward a number of years, and Brian and Stephen have become estranged. Stephen is now a highly ranked fireman like their father and Brian has just graduating from the Fire Academy. This film tells the story of how these men negotiate their feelings towards each other and how they evolve as men within the “family business.” In addition, Backdraft also tackles certain elements of the firefighting world and its approach to masculinity by way of occupational duties, interpersonal firehouse relationships and the career of firefighting in and of itself, using Brian and Stephen’s relationship as the centerpiece.

In Backdraft, Brian McCaffrey is that “fire laddie” Bartley Costello wrote about. The film begins with a sweeping and beautiful Hans Zimmer score, and we witness the young Brian being taken to the scene of a fire alongside his father, played by Kurt Russell. As Brian watches in awe and amazement, dressed in fire clothes that are far too big for his tiny child’s body, the upper level that his father has gone into blasts into huge explosive flames, shooting pieces of the building everywhere and causing the fire helmet worn by Brian’s father to land directly at Brian’s feet. Brian becomes hysterical at his father’s demise, but is quickly scooped up and cared for by the rest of the firemen, but not before picking up the helmet and cradling it with a great deal of tenderness.

The film jumps to 20 years in the future and we are in a bar with a collection of what seem to be young firefighters. The bartender yells out, “Brian, Brian McCaffrey, got some ID?” and we see Brian (William Baldwin) as an adult. He is graduating from the Fire Academy and he is celebrating with the rest of his class. The bartender continues to jokingly harass him, as it becomes clear that this is not Brian’s first time at the rodeo: he has tried the fireman’s route before. “It’s in the blood, Willy,” he tells the bartender, defending his choice to return. Willy responds by listing all the other professional choices that Brian has undertaken that have been “in the blood.” Brian sits there and shrugs. While Brian may have attempted other endeavors, the expression on his face is clear: he self-identifies as the firefighting industry’s prodigal son, and he’s determined to make good.

Statistically, firefighting is an occupation that is passed down through the generations. As Gordon Dillow writes in his L.A. Times article, “Perhaps more than in any other profession, the desire to become a firefighter seems to be passed on genetically, like a hot spot in the family DNA code.” This “biological imperative” firmly in place, Brian’s drive to return to and participate in the industry that originated his sense of manhood is not illogical. In all actuality, it brings with it an almost Freudian sensibility. But the transition is not a smooth one. The film’s text shows Brian going through a series of struggles with the firefighting profession. However, as we see in the end, it is his experiences and accomplishments in the firefighting field that eventually help him establish his identity and make that final conversion from boy to man.

Stephen’s approach is far different than Brian’s, but this is because Stephen has known since day one that he was meant for the firefighter path. He is also older. While it may seem that his age and experience have brought him adulthood and masculine self-reliance, the film proves otherwise. Not only has Stephen failed in his relationship with his wife, he lives on their father’s old broken-down boat near the water, and surrounds himself with relics of the past like a working 8-track player and a wide assortment of classic rock 8-tracks. (He is also, like his father, played by Kurt Russell.) Stephen’s attachment to past relationships and antiquated objects reflect his own stubborn refusal to grow up and evolve into the man he could be. The only place in which he finds success and progress is in the heroic behavior that he displays and is celebrated for in the workplace: the firehouse. In a sense, Stephen is still searching for validation from his dead father by doggedly pursuing a high-ranking career at the station. To Stephen McCaffrey, fighting fires is a divided contract with one part providing the space for him to receive kudos and congratulations for his heroism and firefighter-as-superhero-like achievements and the other part clearing an area for him to work out his anger towards the beast that confiscated his father.

For our protagonist, Brian, the journey of Backdraft is the hero’s journey, sans mythical beasts and travels to alternate dimensions. If you don’t believe me, let’s walk through it. The hero’s journey (made famous by the indomitable Joseph Campbell) consists of 17 stages, but has been slightly condensed by Christopher Vogler in a way that runs consistent with the narrative of this film. Brian McCaffrey begins having returned to Chicago, the ordinary world, and is “called to adventure” through firefighting being “in his blood,” as he points out to Willy the bartender. When the film starts, he has already refused the call once, but has passed that point and has now gotten to the juncture of “meeting with the mentor.”

The “mentor” in this case is Stephen, Brian’s own brother, who, quite literally, will physically train and prepare him for the hero’s journey through fire. While there are several altercations between Stephen and Brian in this process, Brian questioning Stephen’s intentions every step of the way (during one drill, Brian breaks, yelling at his brother, “Let’s just have one drill, lieutenant, not one for the company and one for me!”) the mentoring process is clearly present and in action. While this was certainly a transitive procedure, being passed down from their fireman father, it is nonetheless part of Brian’s process, and his commitment to working with his brother and not against him (as he had done in years previous). This pushes him up to the next stage of the Journey-“crossing the threshold.” This is the stage in which Brian leaves his comfort zone, all his other “trial jobs” behind and commits to what is in his “blood.” He has prepared for it, he has been trained for it, Brian McCaffrey will now enter the world of the firefighter, warts and all.

In this stage, Brian finds “tests, allies and enemies.” While there are many and they vary, all possessing different faces and positions within the firefighting universe, the primary ones are longtime arson investigator Donald “Shadow” Rimgale (Robert De Niro), jailed arsonist Ronald Bartel (Donald Sutherland), and politician Alderman Marty Swayzak (J.T. Walsh). Each of these men serves a different function on Brian’s journey. At the point where Brian’s fire phobia has led him to pursue employment under Rimgale, he finds him to be the most fitting of allies. On the other hand, during this same stretch of time, he experiences the depths of Bartel’s sociopathic need to play games with his compatriots. Swayzak, on the other hand, well… he’s a politician and Brian’s a blue-collar guy. Need I say more? While there are other allies, tests, and enemies in the film, these are the ones that feature most prominently on Brian’s hero’s journey.

Shortly after Brian encounters these figures, it becomes a little tricky. The next stage, the “approach,” is well defined. This is the one in which the work that has been done up until now is used to the hero’s advantage in his Big Challenging Moment. It is also the moment in which the hero and his allies come together to prepare for imminent confrontation. In Backdraft, this becomes complicated due to suspicions that Brian has had about certain other firefighters in the house, including his own brother. However, at the point where his brother’s innocence is confirmed, Stephen’s role becomes mentor-ally, and they move forward together to the next stage of Brian’s journey, “The Ordeal.”

There are varying opinions about what this particular stage in the hero’s journey signifies. Many argue that this stage is not the climax and the climactic sequence comes later. However, in this film, the ordeal and the climax are one and the same, due to filmic design. Within Backdraft, the hero’s ordeal is a series of confrontations with fear, death and masculine traditions. In this section, we watch as Brian conquers fire and becomes the man he’s always wanted to be and the hero he didn’t know he could become. As Rimgale notes earlier in the film, fire is “a living thing, it lives, it eats, it hates.” This rhetoric translates to this scene perfectly. As Brian stands there, trying to decide how to fight this huge inferno, the fire itself rises high above him like a mythical creation, the hose whipping wildly around at the base like an animal tail, flames licking at the ceiling, walls and floor.

Brian tackles his own internal struggles as well as those with his brother and past by grabbing the fire hose, dominating the fires, and establishing a situation in which other firefighters are able to do their job. For the first time in his life he is a man. The gravely wounded Stephen McCaffrey looks at his little brother fighting the fire, and says with pride, “Look at him, that’s my little brother, goddamnit!”

Brian McCaffrey’s hero’s journey continues (in a less uplifting manner in some ways), but he is able to achieve the stages of reward by enacting justice on those requiring it and acquiring his own rewards as well. The end of the hero’s journey is that he has returned “transformed” somehow and has brought something with him. In most mythological versions of this, it is a physical item: a sword, a trinket, a potion. In a Ron Howard film about firefighting, that’s not terribly realistic. Brian McCaffrey’s hero’s journey is completed by his ability to mentor others and be what his brother and his father were to him. As the film closes, Brian is no longer assisting Rimgale. He is back in the firehouse, and he makes a gesture to a new probational firefighter, the identical one that his brother used to make to him about safety in dressing. This, in and of itself is the proof that not only has Brian completed his journey as a hero, he has made the Pinocchio transformation and evolved from boy into man.

Backdraft is a film that looks at the value of the firefighting profession before 9/11. Having that perspective alone is important. It’s a non-political perspective that looks at these men and what they do, who they are, what they mean to each other, to themselves, to their families, adopted and otherwise. It’s a film that focuses on the masculine dimensions that exist within those houses and how things can go desperately wrong and oh-so-right. Some of the sections of this film are perfect reflections of the way that really strong men work together to make a real difference. This is rarely shown in cinema. The use of authentic fireman and authentic fire effects instead of the digital that they were considering using added a layer of reality that this film may not have had otherwise.

So glad you came back for another hot’n’heavy episode of Myth of Macho! Please join me next week! Until then… the brain is a muscle: pump it up!

Stalk me electronically at…. @Sinaphile.