Christopher McQuarrie knows all the secrets: the hilarious deleted scenes, the dramatically different alternate endings, and the tricks to making a kick-ass action sequence unlike any other. As the writer and director of Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation he gave us one of the best action movies of the year. Now he’s telling us all about it in an extensive interview for Crave.

We spoke to Christopher McQuarrie on the phone yesterday to get the scoop on Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, after the junkets had ended, and after audiences have had a chance to see the film. That means we could talk about the whole movie, the way it ends, and the way it connects with previous installments. That means we’re issuing a MASSIVE SPOILER WARNING before we get started.

If you want to know the real scoop on why Simon Pegg’s character never gets to wear a mask, if you want to know what’s going on with Ethan Hunt’s wife Julia, if you want to know why the biggest stunt in Rogue Nation turned up in the very first scene, and if you want to know how the ending to Ghost Protocol changed completely after Christopher McQuarrie came aboard, read on.

Related: The ‘Mission: Impossible’ Movies – Ranked From Worst to Best

CRAVE: I’d like to start at the beginning, of Mission: Impossible anyway. When you were approached to direct Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, was it one of those instances where the story and the set pieces were already in place or did you get to start at square one?

Christopher McQuarrie: It was sort of a mixture of both. We originally started with Drew Pearce and a clean slate. We came up with our list of ideal action scenes that we wanted to do and put them in a semblance of order, and let them drive story. But then after Drew left I rearranged some of the action sequences, which sort of blew up the movie. It changed character motives, it changed certain characters, it introduced new characters, and radically shifted that. It was very important to us that whatever we did, that action couldn’t be driving story. There ultimately had to be a story that made sense despite the fact that we sort of let action get the ball rolling, if that makes sense.

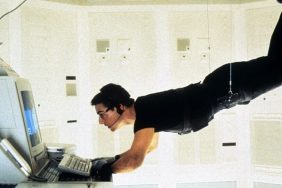

It does, but I’m curious about the way things moved around. For example, the opening plane sequence. You could have made that into a huge centerpiece and instead it’s the one-off mission at the beginning. Is that something that got moved?

That moved back and forth several times. We were always being urged to make that the finale of the movie because everybody knew that was going to be the biggest stunt, and that was going to be the big marketing image. At one of those meetings I said, “What do you care where it goes? You’re going to have the image in the trailer and that’s what really matters. And we also know everyone will have seen that image by the time it comes in the film. So what does it matter where it goes in the movie?” And no one could really come up with an argument. [Laughs.]

And I also know that if it was at the end of the movie it would have to involve the entire team. What happens once Ethan gets on the plane? The sequence would have to continue, and that made the sequence so much bigger, so much more expensive. We wrote it, we budgeted it and we were talking about tens of millions of dollars, and all of it was action for action’s sake. It wasn’t story. It was all action that was being driven by the size of the stunt that got you on the plane. Then what happens once you get on the plane? And none of it really interested us because it ultimately wasn’t what we wanted from the story, which was this game of wits between these two characters.

I really admire the ending of this film. I think the instinct is to always end on the biggest action sequence, but instead I feel like you ended on the most suspense and the most consequence to the actual characters, as opposed the world and whether or not it will blow up.

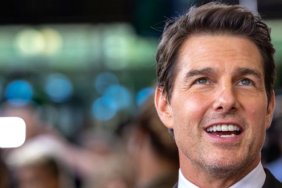

Yes! And believe it or not it was very hard to get there, and only because we kept writing to what we believed a big summer blockbuster movie had to be, and what Mission: Impossible had to be. We were resisting the natural tendency to go where the story wanted to go. […] I came to Tom [Cruise] one night and said, “I think the reason why it’s so hard for us to come up with a big finale for this movie is because those finales are all about killing Lane, and I don’t feel the urge for you to kill Lane. I’m not wanting Lane to die. I feel like it’s telling us to do something else.” And Tom thought about it for ten seconds and said, “You’re right,” and that was the moment in which we let go of everything we thought we had to do in a big summer blockbuster.

So I hadn’t heard about the original plan to kill Solomon Lane. What was the dramatic situation or function behind that?

It’s what you do in all the big summer movies. You have a villain and ultimately your hero confronts the villain and he beats him and kills him. It’s not that there isn’t a plan it’s just that we felt like that was the natural order of things, that that’s where these things are supposed to go, and we were obeying that impulse. But we could never come up with a satisfying ending in which that happened. It always felt like action for action’s sake, and Tom and I simply refused to accept that. The action wasn’t important to us if it didn’t drive story.

And yet – and I’ve admired your touch with action sequences since the shootout at the end of The Way of the Gun – you seem to have a very fine-tuned grasp of how to compose an action sequence, and pace it, and make it clear. Do you have an underlying philosophy about the filming or the editing of an action sequence in general?

It really comes down to, at all times the audience must understand where you are in the sequence and what is happening. And as such I shoot action sequences from inside and outside simultaneously, so that I can shift back and forth between you being in the action and being a spectator to the action.

If you go back and watch the gunfight at the end of The Way of the Gun, you’re predominantly a spectator to those events. I shoot over the shoulder of one character shooting another instead a close-up of a guy shooting a gun and a closeup of the guy getting shot. I keep at all times an understanding of where you are in 360-degree geography. Now that can be abrasive to people who are accustomed to kinetic filmmaking, and it can feel a bit static, and it can feel jarring, and it puts the onus on me to make the on-screen action much more energetic because the camera’s not doing the work for me. If that makes sense.

It does! I’m curious where you developed this idea from, because you had it fully formed in your first film as a director. Was this from watching other films? Where did you get this notion?

It sort of arose organically from writing action and filming action the way I saw it. I didn’t really understand what went into creating what is more commonly considered action photography. I did everything as a writer. Now the consequences of that were something I’ve recently commented on, that when you shoot the screenplay you’re not a director. You’re a writer who just happens to be directing. And so I’ve been taking the lessons I learned on The Way of the Gun and taking them a step further in terms of now trying to bring more of a style to what it is I’m doing. I still feel like I’m learning but I won’t give up what I think is most important about shooting action in exchange for aesthetics. I’m trying to find a way to do what I do and at the same time make it aesthetic. But I won’t sacrifice one for the other.

As a writer I’m curious about one of my favorite lines in the movie. I wonder if maybe you could tell me a little bit about it. “Ethan Hunt is the living manifestation of destiny?”

[Laughs.]

That really made me smile.

I’m glad that it made you smile. That’s one of our favorite moments in the movie and it comes from my tendency to write dialogue specifically for an actor once I’ve attached that actor. So once Alec Baldwin was playing Hunley I really had Alec Baldwin in my head, and hearing Alec Baldwin in my head, [that’s] where that line came from. I remember sitting in the opera when I wrote that scene, because we were still figuring out what the end of the movie was, and it really just… what I needed was a big sell. I needed Hunley to be selling the Prime Minister on who this guy was and doing everything he could to convince him that whatever you do, you cannot escape this guy, and that line arose from it.

Ilsa Faust is just one of the best characters, and what I think I love about her is that she’s kind of a stealth protagonist. Ethan Hunt is in every scene but it feels like she’s the one who has a real story. Can you tell me how that came about?

When I first took the job and I looked at the other four previous movies, I laid them on top of each other and said, where are the holes? What haven’t the other four films done that I could do to make this film unique? And I thought that thing I’d never really seen was a woman who came from the outside, she was not a member of the team, and really kept Ethan off balance. I think they’ve approached that in Mission 2, but that character still felt very much like [she was] torn between two men, and I didn’t want that for the female lead of this movie. And another big formative element of Ilsa is Rita in Edge of Tomorrow, and everything that Tom and I learned from that experience of working with Doug [Liman] and working with Emily [Blunt], and we determined to take that a step further.

I like that Ilsa have romantic tension but they never get together. But a part of me wonders, is that because he’s still married to Julia? Can Ethan Hunt just never have a love interest again?

You know it’s funny, I worked on Ghost Protocol and I resurrected Julia. She was dead in the script when it was handed to me, and I didn’t like that Julia was dead. It took the movie to a dark place from which it could never recover. And I wrote a more detailed scene at the end when Ethan is talking to the members of the team, and they’re all doubting whether or not to return to the field. In that scene I suddenly made it very clear that Ethan realized that he could never have that sort of relationship, and when I see the scene, I still see that idea made clear. To me the language of that scene and the way Brad [Bird] shot it, it tells us that Ethan and Julia are no longer together. They have parted amicably because he has his life and she has hers.

I don’t feel like Ethan is still married to Julia, nor do I believe that Ethan can ever [have] a romantic relationship. I think Ethan has accepted that his lot in life is to be Ethan Hunt, and if anything he is married to his job. Tom and I crafted that farewell as means of, you want to feel what it costs to be Ethan Hunt, and when he says goodbye to Ilsa some part of him would love to have accepted the offer, would love to have gone away with her, but can’t because he has a job to do. And Ilsa, quite rightly, no longer does. So that’s really what important to us, is that their relationship be romantic but not a romance, because again, anything that we did to create a romance between them immediately diminished Ilsa as his equal. Theirs is a relationship that seems really based on a mutual respect and the proficiency with which they each attack the mission.

I’m curious about that ending you wrote for Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol. In that ending Ethan not only sees Julia but he also lets Brandt off the hook, telling Brandt he didn’t get Ethan’s wife killed. Was there ever a draft where Brandt’s reaction was, “Oh, God damn it! I threw away my whole career?!”

[Laughs.] Well interestingly enough, in the draft in which she was dead, he had a totally different backstory that had nothing to do with Ethan and Julia. So that was all a consequence of making that change, saying “Let’s integrate the two stories. Right now Brandt’s story has nothing to do with Ethan’s story, and Ethan’s story is just very dark and very sad, and how do we make all of this a sort of Shakespearean misunderstanding?” That’s very funny. [Laughs.] He could very well have had that reaction.

We’re three films into Benji’s character in this series and he always wants to wear a mask, and he never gets to. Is that just a recurring joke or did you ever consider giving him a moment?

No, we had the moment. In Ghost Protocol there was the moment where he had a mask at the end of the movie and for a lot of real complex production reasons that got cut. The same thing happened here [in Rogue Nation]. There was an entire sequence in which Benji got to wear a mask and it was really fun, and it was a real surprise, and again it got cut. So I have to imagine it will continue to be a recurring joke until the audience has given up on Benji ever getting to wear a mask, and then lo and behold he’ll pull a mask off and it’ll be Benji. It’s hard to give it to Benji! The character has expressed his want and we want to give it to him and we keep running into reasons why we can’t. [Laughs.]

Who was he going to impersonate? Was it Solomon Lane? Because they look kind of similar already.

It’s funny, I never noticed that but people commented on that quite frequently, especially the scene where they’re on screen together. No, he impersonated Alec Baldwin. It was very funny because he pulls off the mask and then, you know, Alec Baldwin is so much larger than Simon Pegg, and Simon reached under his sleeve and pulled a tab and his whole body deflated. He wasn’t just wearing the mask he was wearing a kind of body suit. It was very funny. So it was a great visual gag and it just… we couldn’t do it. We couldn’t leave it in the movie. It just didn’t belong in the film. It took us way in the wrong direction.

What is next for you? I know you were attached to Star Blazers and Ice Station Zebra. Is there any news on those or are you onto something different now?

Those are still assignments that are on my dance card, but I haven’t given a second thought as to what the next thing I’m going to direct is. I tend to finish every movie feeling like, “That was great, I don’t ever need to make another movie again.” And something comes along that catches my interest or I go broke and have to take a job! [Laughs.] But I really haven’t thought about it.

Images via Paramount

William Bibbiani (everyone calls him ‘Bibbs’) is Crave’s film content editor and critic. You can hear him every week on The B-Movies Podcast and watch him on the weekly YouTube series Most Craved and What the Flick. Follow his rantings on Twitter at @WilliamBibbiani.